Why Care About Forecasting?

Danny Hernandez and Frances Ding

This post is a brief intro to forecasting and some motivation for why we’re teaching this class, and why we think Berkeley students should care about forecasting.

Everyone makes bets, and the bets matter a lot.

Some examples of bets that could come up in your own life are:

- Some of you will take some equity from a company, and therefore bet on the success of the company. The good bets are likely to be worth millions of dollars.

- How likely is this relationship to last 20 years? Assuming it lasts, how likely am I to be extremely happy with it?

- Many of you will do research and pursue scientific breakthroughs. Most of the value of research is in a handful of breakthroughs, and you have to choose research directions without knowing whether they will lead to a breakthrough.

- How long will it take me to finish this homework? (Am I actually going to be able to make it to that thing I said I’d go to)

What do we mean by forecasting

In this course we’ll define forecasting as estimating a probability of observing a well defined outcome by some date.

Some examples of well defined forecasts, along with how I arrived at the forecast:

- After looking at the scores from the Big Game for 2 minutes, I’d put a 60% chance on Berkeley winning the next game.

- I think there’s an 80% chance I’ll finish writing this lecture in less than 6 hours of total work. So far I spent approximately 2 hours on it, I currently have a first draft with some feedback. I’ve given similar talks to about 6 different audiences.

- The way I initially valued my equity for Twitch, a startup I joined in 2011, was that I put a 10% chance on Twitch being worth a billion dollars within 5 years. Twitch was valued at 10-20x less than that when I joined, and Instagram had recently been acquired for a billion dollars.

From these examples, we see that most “bets” come down to one’s forecasts (often implicit).

Some bets, and their underlying forecasts, affect the world a lot

Here are some examples:

- The US government and the Gates foundation expected that there was a reasonably high chance vaccines would work against Covid-19 and be developed in time to make a difference. This forecast turned into action through guarantees to buy vaccines from manufacturers (even before FDA approval was given) and in offering funding to scale up manufacturing capacity. Investments on the order of billions probably paid off in trillions of dollars of public good.

- Google, Amazon, Facebook, Stripe, and Bitcoin were bets by founders, staff, and investors. For many people with early involvement these bets returned more than all their previous and future bets combined, both financially and in terms of impact on the world.

- Former President John F. Kennedy said that during the Cuban missile crisis, he thought there was as high as a 50% chance that the situation would escalate to a nuclear exchange.

Hopefully these examples make it clear that forecasting accurately can have a huge impact on the world, which is half the motivation for this class. The other half is that, fortunately, forecasting ability can be improved; it’s not a talent that you either have or don’t have.

It’s recently been shown that getting better at forecasting is tractable

Here is some of the evidence showing that forecasting skill can be improved:

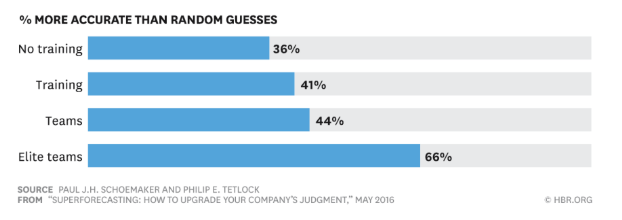

- With a 1 hr training Phillip Tetlock, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, improved participants’ forecasts by 14% (relative to a control group) in a year-long geopolitical forecasting competition. Some examples of forecasts that were in the competition: What is the probability the U.S. will sign the Paris Accord?; Will the U.S. deploy ground troops in Syria?; etc. This research was mostly done in the last decade, so it’s only been leveraged a modest amount.

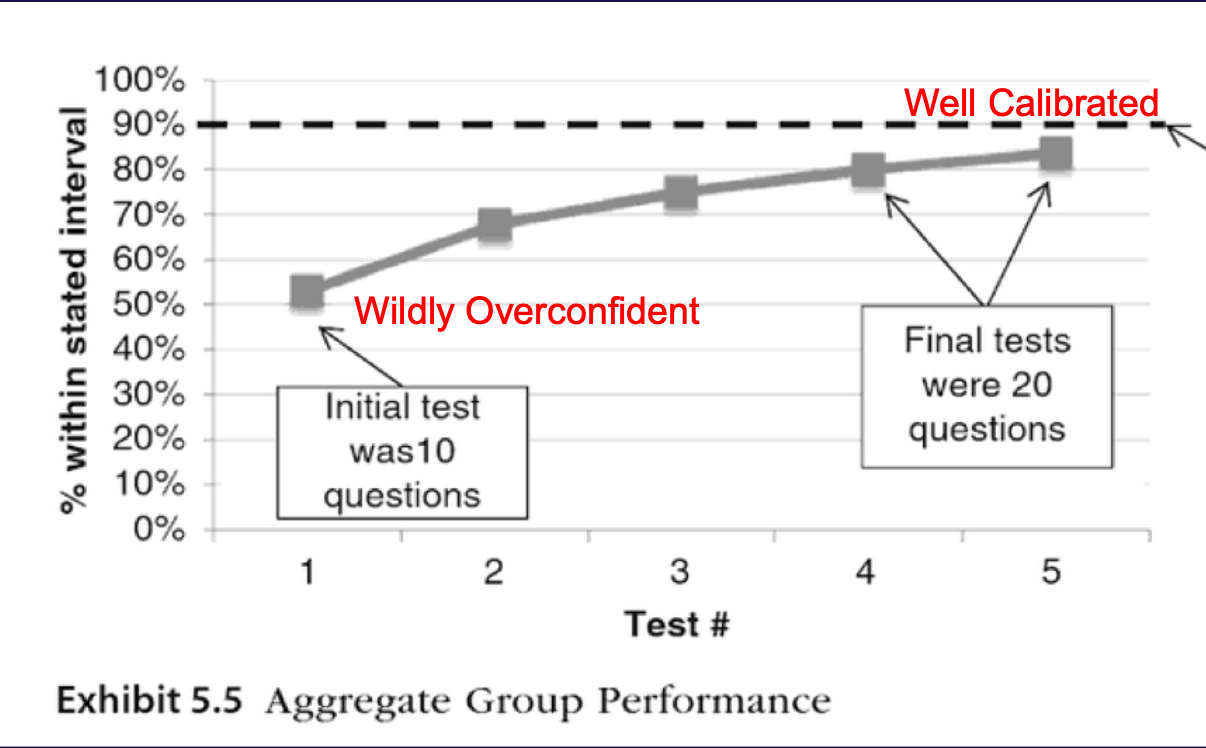

- One desirable property of forecasts is calibration. When someone is “calibrated”, that means the events they forecast with 90% probability really occur 9 times out of 10, and the events they forecast with 50% probability really occur half the time, and so on. . Douglas Hubbard found that most people can become calibrated in about 2 hours of training.

- By measuring forecasting performance and putting the most accurate forecasters together on teams, Tetlock was able to assemble teams that beat professional CIA analysts, who had access to classified intel.

This shows that there is significant variation in forecasting skills beyond what can be conveyed during a 1-hour training session. In this class, we’ll help impart those skills. With deliberate practice, we think many of you can reach the level of these elite forecasting teams.

Now let’s practice a little.

(In class this will be a group activity.)

For each of the following questions we’ll estimate an 80% confidence interval. This is an interval you think has an 80% chance of containing the true, known answer. Ideally, if we went through dozens of questions like this, 80% of the time your confidence interval would contain the right answer (importantly, you shouldn’t aim for the confidence interval to have the right answer 100% of the time!). We’re asking for a confidence interval and not just a point estimate because it will provide you with better feedback on how to improve forecasts than if you just gave a single number point estimate.

- UC Berkeley surveyed English Majors graduating in 2020.

- What is the fraction of graduates who responded seeking employment (having trouble finding a job)?

- Among graduates who reported salaries, what was the average salary?

- Austria’s Organ Donation Rate is 99.98% (the policy is that by default, you consent to organ donation, but you can opt out). What is Germany’s organ donation rate (the policy there is that you have to voluntarily opt in to donate)?

We’ll add the answers to this post after class.